Anisha just inherited 50 Lakhs from her Grandma. She’s a smart young woman and she knows she should invest this money for a brighter future. But the question is how? Should she invest the entire 50 Lakhs in the market right now? Or should she put it in a liquid fund and do STPs (systematic transfer plans) into equity funds? Which will give her higher returns? And what if the market were to crash shortly after she invested? She would never forgive herself for shrinking such hard-earned money?

It’s at this point that one faces a dilemma when investing. When faced with this decision, many investors prefer to spread the investment out. So that instead of buying at a single price, the level at which they invest in the market is averaged out. This kind of investment approach is known as “rupee-cost averaging”. But it can come with a cost.

Packing In Protection

The idea of rupee-cost averaging is to provide some protection against the possibility of the market dropping sharply soon after the money is invested. As no one wants to mistakenly buy at the top of the market.

Instead of the entire investment suffering this loss, only the invested portion does. The rest, in theory, is then invested at lower prices. In this way, rupee-cost averaging can work well in a falling market.

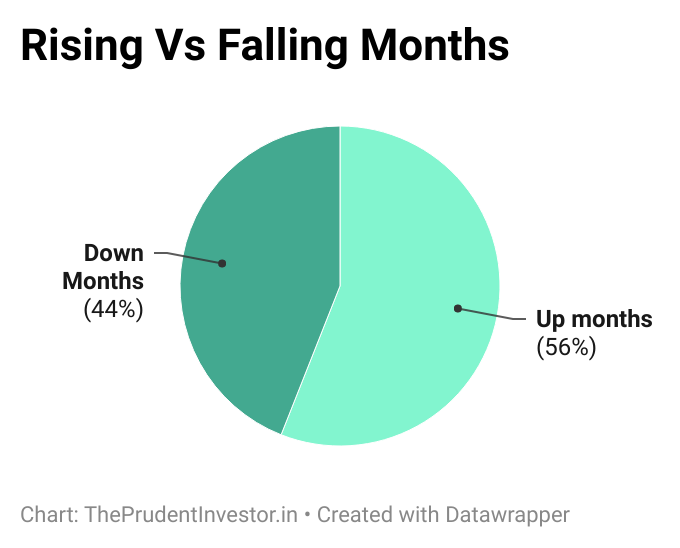

The problem is: markets tend to go up more often than they go down. So with rupee-cost averaging you’re more often likely to buy when prices are rising rather than decreasing; an inefficient strategy.

Skewed allocation

Another downside to rupee-cost averaging is that it will change the asset allocation of your existing portfolio until the new amount is completely invested. That is, any extra cash you hold could alter your overall mix of investments and make it different from what you planned originally.

For example, say you have a portfolio that’s 70% shares and 30% bonds. Now imagine receiving a lump sum that’s equal to this portfolio. Your new portfolio will be split into 35% stocks, 15% bonds, 50% cash.

This is a very different allocation and is highly unlikely to align with your goals. This is averse to tried and tested investment principles. Given the immense research showing the importance of asset allocation to investment results, this could lessen your chances of investment success.

Cash earns a paltry return and will drag down your portfolio’s total return. And if the cash doesn’t get fully invested (possibly because you forgot about it or got panicky by a market decline) this cash drag can persist forever, leading to permanently lower returns.

Better than nothing

So, is rupee-cost averaging useless? To be honest, no. It can be a perfectly valid strategy because it can hedge against regret. You might get lucky with your timings too.

No one likes the idea of investing a significant sum of money, only to see the market drop immediately afterward. For some, this fear of regret leaves them paralyzed. They wait until they feel confident about the market. Which may never happen. For these investors, rupee-cost averaging may be a way to overcome that paralysis and at least invest something.

This insurance against regret comes at a cost. Usually, rupee-cost averaging will lead to lower long-term returns, implying investors would have been better off investing their funds lump sum. But if you’re scared of a market downfall, rupee-cost averaging might at least provide you with protection against regret: especially if the alternative is not investing at all.

Should I invest this money immediately or over time?

We understand the fear many investors may have around investing their money. There is a lot at stake. Lakhs, maybe Crores of Rupees. What if the market crashes right after you invest? Wouldn’t it be better to average-in over time (rupee-cost averaging/RCA) to smooth out any unlucky timing on your part?

The main reason Lump Sum outperforms RCA is because most markets generally rise over time. Because of this positive long-term trend, RCA typically buys at higher average prices than Lump Sum. In those occasional situations where RCA outperforms Lump Sum (in falling markets), it is very hard to stick to RCA. So, the times when RCA has the largest advantage are also when it is the toughest for investors to stick to their plan.

The STP or lumpsum debate is actually one of market timing. Doing an STP indirectly assumes that you can time a market high; it is the only scenario that justifies doing an STP over a lump sum. If you don’t think you can time market highs, then do not STP.

Why is STP an outcome of market timing? You see, STP will only work when the average NAV over the next 12 months is lower than today’s NAV so that you can buy at a lower average price over the year than today. An STP investor is making a complex claim that the NAV will be on average lower over the next 12 months while he/she is purchasing units after which it will go up.

Lumpsum makes no market timing assumptions. It is the simpler option.

In God we trust, All others must bring data

We ran a simple backtest to see what the historical data suggests. We started with HDFC Top 100 Mutual Fund data going back to 2003. Over the past 18 years, the market has made a new all-time high in 63 months. In each of those months we set up two investments:

1, Investment in a liquid fund and then STP into HDFC Top 100 over one year.

2, Invest in HDFC Top 100.

After one year we see which investment did better. Of the 63 instances when we set up the STP vs Lumpsum race, the Lumpsum investment outperformed 57 percent of the time. More importantly, investing in a lump sum would have returned an average of 10.64 percent, while one year STP returned on average 9.11 percent after one year.

What happens if you decide to run SIPs/STPs instead of lumpsum? You lose out on the following:

- Instead of deploying the entire amount (into equity and thereby compounding), you are deploying in installments. So, you are losing time and starving yourself of the power of compounding like it can with lumpsum.

- You will have your funds sitting in your bank account until completely deployed or have them in a liquid fund with STP and paying tax on such switches throughout the STP period.

What Should I do?

We can’t foresee the future. We cannot know in advance whether lump-sum investing or rupee cost averaging will lead to higher yields.

In investing, it is crucial to understand the limitations of our knowledge. Don’t get swayed by investment news which makes market predictions. As Warren Buffett says, a stock market prediction tells us more about the person predicting than it does the future.

Even if we knew where the market would stand a year from now, we still wouldn’t know whether lump-sum investing or rupee cost averaging would lead to a better result. Why? Because the outcome would depend on how the market performed during the year. If it fell and then rose, rupee cost averaging would take advantage of the lower prices. If it rose and then fell, lump-sum investing would lock in the lower price at the beginning of the year.

Avoiding Losses Favors Rupee Cost Averaging

Some investors are more concerned about losing money than about maximizing returns. If your concern is the preservation of assets, rupee cost averaging might be the better approach.

Consider Your Risk Tolerance

When it comes to investing, our emotions can cause us trouble. This applies both when we get scared or excited. Either can lead us astray. The aforementioned study highlights this fact:

If the investor is mainly concerned with minimizing downside risk and potentially feeling regret (resulting from lump-sum investing immediately before a market downturn), then RCA may be useful. Of course, any emotionally based concerns should be carefully weighed against the lower long-run returns of cash compared with stocks and bonds and the fact that delaying investment is a form of market-timing (something few investors succeed at).

If an investor goes all in with a lump sum investment and the market falls, it impacts them negatively for years. To prevent this outcome, rupee cost averaging may be the better approach. However you choose to invest a windfall, it’s important to think about the emotional side of investing as well, not just the math.

Follow a Plan

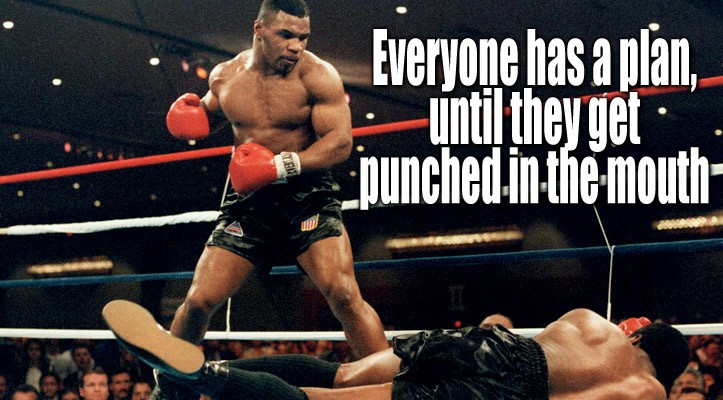

One should always have an investment plan. If you decide to rupee cost average, make a plan, write it down and stick to it. For example, you may decide to rupee cost average over a year. You’re going to take one-12th of your funds and invest it monthly. Make sure you write it down and stick to it no matter what.

Sticking to a plan assists us in sidestepping market timing. No one knows how the market will perform in the future. So it’s critical to commit to a plan. We should do the same with our asset allocation plan and our approach to rebalancing.

Don’t forget the tax implication of STP

A significant consideration is the tax implication of an STP. When you invest in a liquid fund and switch funds into an equity fund, then each switch will be treated as a redemption of the liquid fund. Since liquid funds are non-equity funds they will be classified as Short Term Capital Gains for up to 3 years and will be taxed at your peak rate of tax. Even beyond 3 years, gains are still taxed at 20% after considering indexation. This will certainly impact net returns.

When deciding between investing all your money now (lump sum) or over time (rupee cost averaging), it is usually better to invest it now.

Generally, the sooner you deploy your capital, the better off you will be. We say “generally” because the only time when you are better off by doing RCA is when averaging into a falling market. However, it is precisely when the market is falling that you will be the least enthusiastic to keep buying. It is tough to fight off these emotions, which is why the times when it is best to RCA, most investors are unable to stick to the strategy.

If you are still uncomfortable investing your lump sum today, the problem may be that you’re investing in a portfolio that is too risky for you. Consider placing this money in a more conservative portfolio now and moving on with life. Say you want to be invested in 100% stocks (but you are worried about a market crash) it would be better to put it in now into an 80/20 stock/bond portfolio instead of rupee-cost averaging into an all-stock portfolio over time.