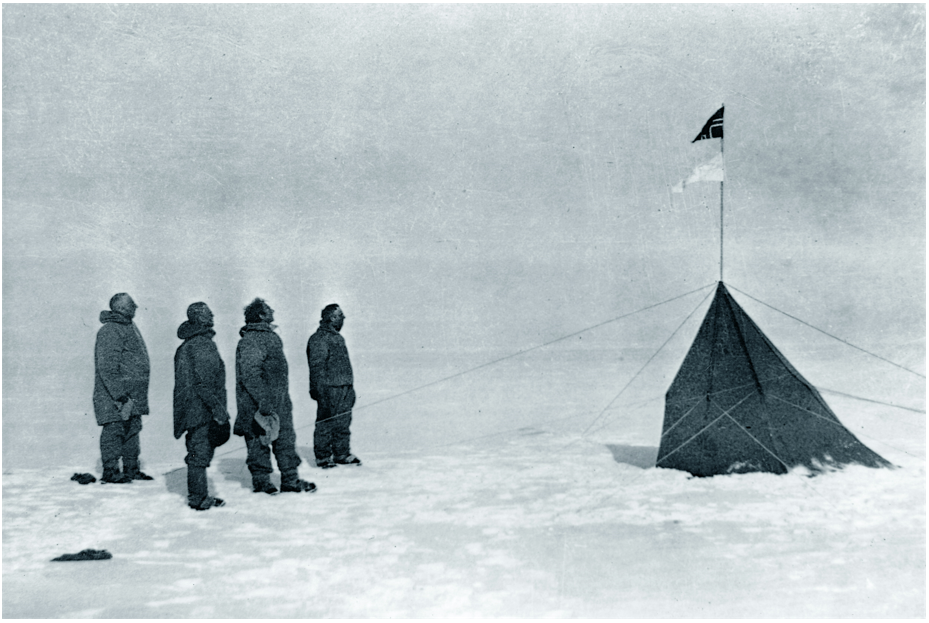

In November 1911, two rivals set out on a race to reach the South pole: Captain Scott from Great Britain, and Amundsen from Norway (a. k. a. the Last Viking). They began within days of each other, a 1500-mile race against time. One team would return victorious. The other would not return.

If you read their journals, you would never guess that the two teams made almost the same journey under almost the same conditions. On the days with good weather, Scott would drive his team to exhaustion. On the days with bad weather, he would hunker down in his tent and lodge his complaints in his journal.

On one such day, he wrote, “Our luck in weather is preposterous. It makes me feel a little bitter to contrast such weather with that experienced by our predecessors.” On another, he wrote, “I doubt any party can travel in such weather.”

But one party did.

On a day having a similar blizzard, Amundsen recorded in his journal, “It has been an unpleasant day, with storm drift and frostbite, but we have advanced 13 miles closer to our goal.”

On the 12th of December, the plot thickened. Amundsen and his team got within 45 miles of the South Pole, closer than anyone who had ever tried before. They had traveled some 650 grueling miles and were on the verge of winning the race of their lives. And the icing on the cake, the weather that day was in their favour. Amundsen wrote, “The surface is as good as ever. The weather is splendid and calm with sunshine.” They were on the polar plateau. They had the ideal conditions to ski and sled their way to the South Pole.

With one big push, they could be there in a single day. Instead, it took three days.

Why? From the very start of their journey, Amundsen had insisted that his party advance exactly 15 miles every day, no more and no less. The final leg would be no different. Rain or shine, Amundsen would not allow the daily 15 miles to be exceeded. While Scott allowed his team to rest only on the days when it froze and pushed his team to the point of inhuman exertion on the days when it thawed. Amundsen insisted on plenty of rest and kept a steady pace for the duration of the trip to the South Pole.

This one simple difference between their approaches can explain why Amundsen’s team made it to the goal, while Scott’s team perished. Setting a steady, consistent, and sustainable pace was ultimately what allowed the party from Norway to win.

And by the way, this is the phrase they used, “To reach their destination without particular effort.”

What an absurdity, without particular effort. Such an impossible goal, but that’s how they approached it.

Amundsen led his team to victory. They reached about 30 days before Scott’s team arrived, demoralized and exhausted. Their approach exhausted them. So, they didn’t achieve the goal and they were burnt out. They were so exhausted that they made poor choices in their approach to action. And they died on the way home. Amundsen’s team was not only victorious but also thrived through the experience.

There is a false economy of powering through. The goal is to find a pace that feels, if not effortless, just doable. You want the consistency of effort, a pace that sustains.

There’s a military phrase, which goes “slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.”

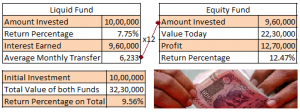

How can we apply this consistency of effort and sustainable pace to our investments? Let’s understand the pricing phases of the stock market.

Over long time periods, the markets usually go through three pricing phases: Bad, Good, and Great prices.

Thankfully, they are not equally distributed in which case SIPs wouldn’t make any sense.

- Bad Price: happens a small portion of the time (~10-20% of the time*)

- Good Price: happens most of the time (~60-80% of the time*)

- Great Price: happens a small portion of the time (~10-20% of the time*)

*Please note that these are rough estimates using history as a guide

Some of us tend to get upset during a market fall (think March 2020) and stop our SIPs. Your SIP would have certain periods where it purchased equity at BAD prices (which you certainly didn’t know at that time). So, you will need some periods where you buy at GREAT prices to compensate for this.

Unfortunately, GREAT prices are available during a market fall. If you stop your SIP during a market fall, you don’t get to buy at GREAT prices. This means you don’t get to compensate for the few periods where you bought at BAD prices.

Since this is how an SIP works, stopping your SIP is a double setback. Overall, your SIP buying ends up looking like 60-80% good price + 10-20% bad price + 0% great price.

As a result, you end up with lower returns despite having a long investment duration due to a fearful decision you thought was going to protect you.

So, it is important to understand that continuing your SIP during a market fall, though it may seem highly counterintuitive and painfully difficult is essentially the critical reason why an SIP works over the long run.

Final Thoughts

Overall, the idea of an SIP is to provide good returns over the long term by intentionally following the Amundsen approach: steady, consistent, and sustainable even though it includes buying at bad prices for a small percent of the time to avoid the Scott approach of firing full throttle during good times and hunkering down during bad times which will lead to erratic and inferior returns. With SIPs, the small percent of inferior buys is amply overcompensated by the small percent of great buys carried out during market falls.

So, the entire success of an SIP depends on whether you continue your SIPs in a disciplined manner over the long term without panicking and stopping them during a market fall.